As Warp Records celebrates its 25 year anniversary, Defected’s Ben Lovett takes a closer look at the story behind of one of the most important and influential labels of all time.

Warp Records was firmly in veteran DJ-producer Chris Duckenfield’s thoughts last September when he spoke to us for a feature on Sheffield’s ongoing electronic legacy. Warp, assuredly, is pride of place within that legacy but also represents a pivotal, open chapter in electronic music’s wider global history. “It’s at Warp I cut my teeth as a ‘proper’ DJ and enjoyed my first forays into the studio. I owe it everything!” Duckenfield explained. “They’re still easily one of the most interesting indie labels on the planet. Flying Lotus, Grizzly Bear, Battles – it’s the same spirit of championing mavericks they’ve always had.”

It is thrill-seeking pioneer spirit that has brought Warp confidently on to its 25th anniversary in 2014, some achievement considering the frequent, destabilising vagaries of the dance music industry. This September, Warp will journey to Krakow, Poland where it plans to fully commemorate its journey so far by aligning with renowned avant-garde collective Sacrum Profanum. The collective’s annual, eponymous festival will see Warp stalwart Squarepusher presenting a new live show alongside pre-eminent European chamber ensemble Sinfonietta Cracovia, and the London Sinfonietta performing their acclaimed interpretations of Warp artists Boards Of Canada and Aphex Twin, hugely influential US composer Steve Reich and others (‘Warp Works and 20th Century Masters’).

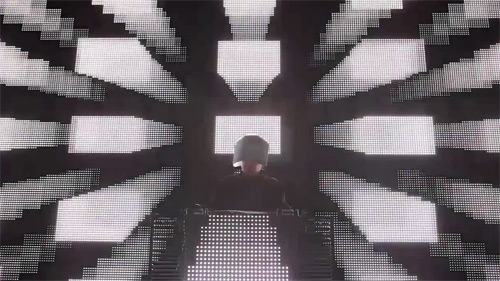

More exciting, perhaps, than that, Warp will use its Polish adventure to throw a once-in-a-lifetime birthday party focused squarely on the future and what the next 25 years may hold for the label. Both Battles and Autechre are set to introduce new material at their first live shows in nearly three years (and only live shows of 2014) and seasoned Bjork collaborator LFO will drop a rare as hens’ teeth AV set. Elsewhere, Hudson Mohawke, Rustie, Darkstar and patten all play, demonstrating iconoclastic verve via everything from abyssal bass warbles and twisted beat-scapes to nu-psychedelic groove and cacophonic warehouse rave. The future looks bright and deliciously unhinged.

“Why are we still here after 25 years?” Leah Ellis, Warp’s Head of UK PR ponders. “We care about our artists and take their lead on their creativity. We encourage them to come up with their own ideas. Another aspect is the music...it is quality not quantity.”

It didn’t feel that long ago that Warp Records celebrated 20 years in the game, primarily with marquee international shows from Broadcast, Aphex Twin and Flying Lotus, and an epic, objet d’art ‘best of’ boxset. The emphasis was very much on what Warp had realized up until that point. The label was founded, rather informally, in the back room of a Sheffield record shop [FON] by local underground stalwarts Steve Beckett, Rob Mitchell (who died from cancer in 2001) and Robert Gordon. It was the latter, too, alongside fellow Sheffield mainstays Winston Hazel and Sean Maher who, as The Forgemasters, provided Warp’s bleep-y hardcore techno debut Track With No Name in 1989.

The track was funded by a government Enterprise Allowance Grant and distributed via borrowed car. “At the time we didn’t think we were setting up a label necessarily” Beckett mentioned in an interview in 2012. “It was more about, ‘Let’s do this 12-inch and see if it can have an effect’, like we were seeing in guys likes 808 State and Unique 3. It was all orientated to the dance floor rather than the label side of things.”

Warp’s founders found other creative ways to fund their expansion, selling tickets for gigs at Sheffield University to generate sufficient cashflow. FON was subsequently refit as a new record store, also called Warp. Importing futuristic dance from Detroit and Chicago it reported round-the-block queues as more and more of Sheffield started to embrace electronic music’s nascent revolution. The mechanised house and techno of labels Trax, Underground Resistance and Transmat would also influence Warp’s next releases – barn-storming outings for Tricky Disco, LFO and Sweet Exorcist.

Warp’s profile rapidly escalated. Radio 1 legend Jon Peel called up to declare his affections and successful club label Rhythm King, with a track record for shaping raw dance cuts into sleek, commercial bullets, offered a lucrative tie-up. “They made an approach to do a label deal and we thought we’d done the deal of the century” Beckett commented. “We signed away everything for £10,000 and just walked out of Rhythm King going ‘Yes, we’ve done it’.”

Alas, Warp’s contract with Rhythm King off-shoot Outer Rhythm didn’t quite go to plan. LFO and Tricky Disco motored up the mainstream charts but all unit sales were heading to Rhythm King. Warp’s sleeve logo too was, much to Beckett’s chagrin, smaller than Outer Rhythm’s. It was a difficult introduction to the music business. “You’re into your little mind-set going, ‘Fucking some idiot’s given us 10,000 quid to release our records,’ and then not realising that after a while you’re selling 100,000 records and you’re not seeing a penny and going, ‘Hold on...my God, what have we done?’” Beckett reflected. Amidst all of this Gordon had left the Warp family on bad terms.

Beckett and Mitchell turned to Mute Records’ Daniel Miller – who had separate ties to Rhythm King – to help them withdraw from their contractual hell. Once they were back in charge, they committed themselves to remaining fiercely independent. And on Miller’s recommendation made long-term artist development a priority, whilst extending their various musical interests beyond the UK. Consistency and permanency were vital. In 1991, Warp released the first album by a British techno act, LFO’s Frequencies, and from that point onwards continued to build a diverse but loyal family. “It [Frequencies] pulled us out of the trough, where we were just completely skint with no royalties” Beckett reflected. “It was the point where we turned ourselves into a record label. We really started clocking that was the way to have a bit of longevity and build artists.”

Since then, Warp has gone from strength to strength. The label moved to London in 2000 but its remit has remained the same. A unique, challenging and ultimately rewarding catalogue of electronic work from the genre-defying likes of Aphex Twin, Darkstar, Squarepusher, Hudson Mohawke, Nightmares On Wax and Boards of Canada is at the heart of Warp’s essence. The label’s recent output, too, does nothing to diminish that maverick electronic spirit. Whether it be through releases by Oneohtrix Point Never, an electronic experimentalist based in the world of contemporary art, or those by London singer-songwriter Kwes, brazenly orbiting electronica, hip-hop and indie, Warp’s handle on its future is remarkable. Hype has inevitably built and built but if there was any pressure to deliver on rampant audience expectation Warp doesn’t show it.

How exactly has Warp evolved over the years? “I think advancements in technology have helped us and the artists to explore more creative techniques” claims Ellis. But then the label was always pushing its limits from the very beginning, and not just those of an aural persuasion. Those early vivid Phil Wolstenholme-designed vinyl sleeves have led on to a variety of innovative projects exploring the relationship between music, film and art. The output of Oneohtrix Point Never is an obvious example, so too the activity of Warp Films (launched in 2004, and with award-winning motion pictures under its belt including the Richard Ayoade-directed, bespoke Arctic Monkeys-soundtracked Submarine) and recent art-sound collaborations with London’s Science Museum, Tate Britain and the British Film Institute.

Once mustn’t forget Warp’s prowess in music videos either, memorable shorts for Aphex Twin (1997’s Come To Daddy, 1999’s Windowlicker) and Flying Lotus (2012’s Until The Quiet Comes) accelerating the careers of directors Chris Cunningham (who progressed to work with Madonna) and Kahlil Joseph (who won a prestigious Sundance Film Festival Award). All channels of communication are open.

A point Warp Records marketing head Steven Hill heartily acknowledged in an interview last year, when discussing the label’s similarly innovative approach to promoting. “Digital is a big thing but I think, much broader than that, the way you interact with an audience and an artist is really different [today]” he said. “The nature of communication is different which has been enabled by technology and awareness. You can actually have a conversation and stimulate conversation.”

The label’s idiosyncratic personality has therefore become more important than ever, as Ellis testifies: “Our personality? It is all about creativity, once again. Because we are a small label in terms of workforce we get to work really closely with artists and fans.” And so Warp is able to nurture and protect the crazy, beautiful spirit that has united and defined it for the past couple of decades - and-a-half.

Legendary Sheffield DJ-producer Richard ‘Parrot’ Barratt, who ran iconic local night Jive Turkey with Winston Hazel during the late Eighties, believes that Warp’s founders were always destined to succeed. “Rob and Steve were bandy sorts before starting the shop and label” he reminisces. “I think that background gave them a good insight into the minds of the new audience that sprang up for electronic music in the late Eighties. Sheffield had already found its electronic feet through Cabaret Voltaire and The Human League. Rob and Steve understood that there was an appetite that, although stimulated by dance music, went beyond dancing. A whole new market appeared; people were turned onto electronics via house and ready to try new forms. Rob and Steve got that in a way that they may not have done had they been strict dancefloor enthusiasts or soul heads.”

Long may Warp’s open-minded escapades and adventures continue....

Words: Ben Lovett

For more details on Warp’s 25th anniversary plans, head to http://warp.net/records/general/warp25