“The Belgian underground club scene was already forming its own electronic sound way before American house imports hit the streets”

So says Bart Van Neste, AKA long-term Belgium club hero Red D and one half of transcendent electronic duo FCL. We’re discussing the history of electronic dance music in his homeland. Van Neste continues: “Those American records were never really that big to my knowledge. The sound that would become known as New Beat was already being shaped during the early Eighties – in venues like Ancienne Belgique in Antwerp and Boccaccio in Ghent. Very much like the Paradise Garage in New York and Muzic Box in Chicago, the DJs in those clubs were looking for stuff to keep feeding their dancefloors after the demise of disco.”

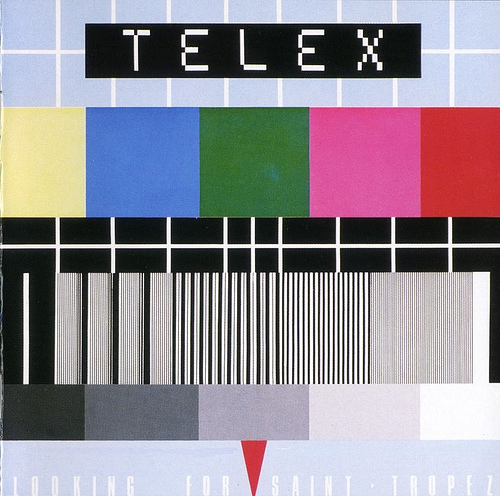

Belgium had already established a robust electronic sound with frontier bands such as Telex and Pas De Deux. The latter, former Eurovision Song Contest entrants, had a string of successful singles during the early Eighties, including 1983’s ‘Manimeme’. Belgian synth-poppers Telex had started even before that, 1979 debut album Looking For St Tropez followed by several more during the next decade and, such is their legacy, further output in the Noughties. “The darker, more electronic sound was what people were looking for” Van Neste reflects.

In turn a hybrid of European New Wave synth-punk and post-industrial production would rise to prominence in Belgium during the early Eighties. The sound was referred to as EBM (Electronic Body Music) – a tag cemented when Belgian band Front 242 used it to describe their 1984 EP ‘No Comment’. Before that, Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hutter had used the label in 1978 to describe the more physical sounds of their album The Man-Machine. Alongside Front 242, the music of bands Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, DAF and Die Krupps was seen to drive the EBM phenomenon forward, combining everything from distorted vocals and repetitive sequencers to industrial sound effects and sci-fi film samples under danceable 4-4 beats and synths.

It wasn’t to last, however. As the decade progressed, Belgium began to embrace an exciting evolution of its foundational electronic sound. New Beat, particularly prominent in Belgium during the mid and late-Eighties, was widely seen to combine elements of Chicago house, underground pop, New Wave and slowed-up Body Music.

To Van Neste, the US influences were there but not so prominent. “I think the biggest influence from across the Pond was acid house. The acid squelch quickly became part of the New Beat sound, as did the 808 and 909 [Roland TR drum machines] but that was more because those things were available than out of some form of imitation. Some slower Chicago records became big in the New Beat scene but they were always a minority. The UK piano house sound never really took off here either. Belgium was always about darker sounds.”

The seeds of New Beat were largely planted and spread from within - in Antwerp and Ghent. Local DJs and their crowds had a growing requirement for grooves built upon slow, booming bass – this often came through playing 45rpm EBM cuts at 33rpm. Many commentators cite DJ Dikke Ronny (‘Fat Ronny’) as accidental inventor of the genre, having played A Split-Second’s EBM classic ‘Flesh’ at the Ancienne Belgique at 33rpm with his turntable’s pitch control set to +8.

Before long there was a raft of committed, game-changing New Beat producers. “One of the key names was a production team called Morton, Sherman [AKA Herman Gillis, designer of iconic Belgian filtering hardware, Sherman Filterbanks] & Belucci” Van Neste recalls. “And there was a young guy called Maurice Van Engelen, who released a ton of New Beat on his Antler/Subway label. He later became known as Praga Khan [in turn forming duo Lords Of Acid]. And of course there was also the early R&S records by David Morley, Cisco Ferreira [of Advent fame] and loads more....”

It was at this time that Van Neste, 13, made his first electronic discoveries. The year was 1986. A Walkman grabbed from a football teammate promptly shoved him towards Belgium’s exciting new sonic frontier. And when Van Neste found a new Ghent station playing electronic music specifically he was totally hooked. Fast forward a few years. “It was really around 1990-91 that I started getting tapes from clubs and meeting older school mates that had cars and could take me with them to Boccaccio and La Rocca [a club in Lier near Antwerp]. After that it was no holds barred trying to find out more about these sounds and buying my first 12-inch release.”

Into the Nineties and New Beat started to lose its way. Commercial motives accelerated, Belgian chart-topping bands and folk singers alike attempting to make New Beat versions of their back catalogue highlights – most notably celebrated Belgian accordionist Rocco Granata (with single ‘Marina’). The underground moved on, R&S leading the line with a string of key releases in association with Detroit kingpins like Derrick May and Stacey Pullen; not to mention New Yorker Joey Beltram. But Belgium’s own studio talent had gone quiet.

“In the early Nineties, Belgium became a tastemaker through labels, clubs and parties, rather more than making the music” Van Neste urges. “It was only around1992-93 with the ‘Hoover’ sound and the early trance music that Belgium’s studio wizards came to the forefront again.” Typically, Van Neste’s first vinyl purchase was DJ Hooligan’s 1992 lick ‘It’s A Dream Song’, a German cut responsible for kicking off Europe’s wider hard-trance renaissance.

“The underground trance sound was really big and very creative over here in the Nineties” Van Neste says. “But coming into the Noughties, Belgium’s studio output dwindled again. Starting around 2000 or 2001 I’d have a hard time finding a true Belgian sound, and this has continued up to today really. I’d have to say that 2 Many Djs were Belgium’s pride internationally through the Noughties. In house, apart from Raoul Belmans and his Swirl People, Belgium never really had big things going on.”

So where is Belgium at today? It is clear EDM has a large part to play, as it does across much of the world. Similarly, Belgium isn’t unique in having lost many of its regional sounds and scenes through the advent of the internet. There are, as always, pockets of interesting deviation but the country as a whole has lost significant identity, as have many of its key cities. Van Neste is attempting to address that. “I’m happy to say that the last couple of years things have changed for the better. I’d like to think that my own We Play House Recordings with San Soda [fellow DJ-producer Nicolas Geysens], FCL [Van Neste alongside San Soda again] and others have helped spark the house thing in Belgium, next to a load of really credible and cool promoters who are throwing parties all over the place.”

Van Neste elaborates further: “I recently had a discussion with someone who’s also been in the game for 25 years or so, and he claimed Belgian club culture is well and truly dead, whereas I argued it’s far from dead...just evolved from club-based to promoter/festival-based. When it comes to really good clubs with their own identity and brave programming I think Belgium is a bit of wasteland and with only a handful of institutions like Fuse, La Rocca, Cafe D’Anvers and Decadance left. But the ‘one-off’ scene, with different promoters throwing parties in various locations, is very much alive.”

Van Neste laments the lack of government support for Belgium’s contemporary club scene, as well as the enforcement of difficult legislation making it virtually impossible for start-up venues to thrive. In which case it doesn’t seem likely the balance of power in Belgium will shift back from festivals to clubs any time soon. “The legendary Belgian club scene where you could go out from Friday night till Tuesday morning is well and truly gone” Van Neste suggests. “But the number of people doing something with dance music has never been this high, so as with all things there are upsides and downsides.”

All of which prompts an obvious question about where Van Neste’s homeland heads next? There are some interesting new club ventures in Antwerp and Brussels; the latter, particularly, home to promising debutante Bloody Louis as of last September. Van Neste’s home city Ghent, too, continues to convey some of Boccaccio’s unique spirit (the revered club finally closed as Boccaccio Life International in 1993) in that its musical playlist remains refreshingly broad. If the city’s most famous sons, 2 Many DJs and The Glimmers, amplified Boccaccio’s spirit over the previous decade then a number of new artists and dancefloors have maintained it for this one.

“I’m kinda hoping kids will go back to the age-old practice of picking their favourite club” Van Neste offers. “At the same time, I hope those clubs will once again select a couple of good residents and not cram the line-up with weekly guests spinning one-and-a-half hour sets. That is the only way for musical longevity in our scene...that I am 100% sure of.”

And what about both FCL and Red D’s longevity? “I’ve never changed my style for one second in the last 20 years, and that in itself is a tribute to the true Belgian spirit” he starts. “We’re underdogs and we sink our teeth in anything interesting coming our way, and every now and then we add something interesting ourselves. A true Belgian does not follow trends, because [Van Neste smiles] we were never hip enough to set trends ourselves....”

Words: Ben Lovett

Defected presents FCL In The House is out 25 January (2CD, digital and vinyl sampler) on Defected Records - order from iTunes and Amazon