WORDS: NICK GORDON BROWN

In our recent feature Booked: Dance Music In Print, we highlighted the pioneering work of Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, both as authors of an essential triumvirate of books (Last Night A DJ Saved My Life; How To DJ Properly; The Record Players); and as publishers via the spin off to their ground breaking DJHistory.com website.

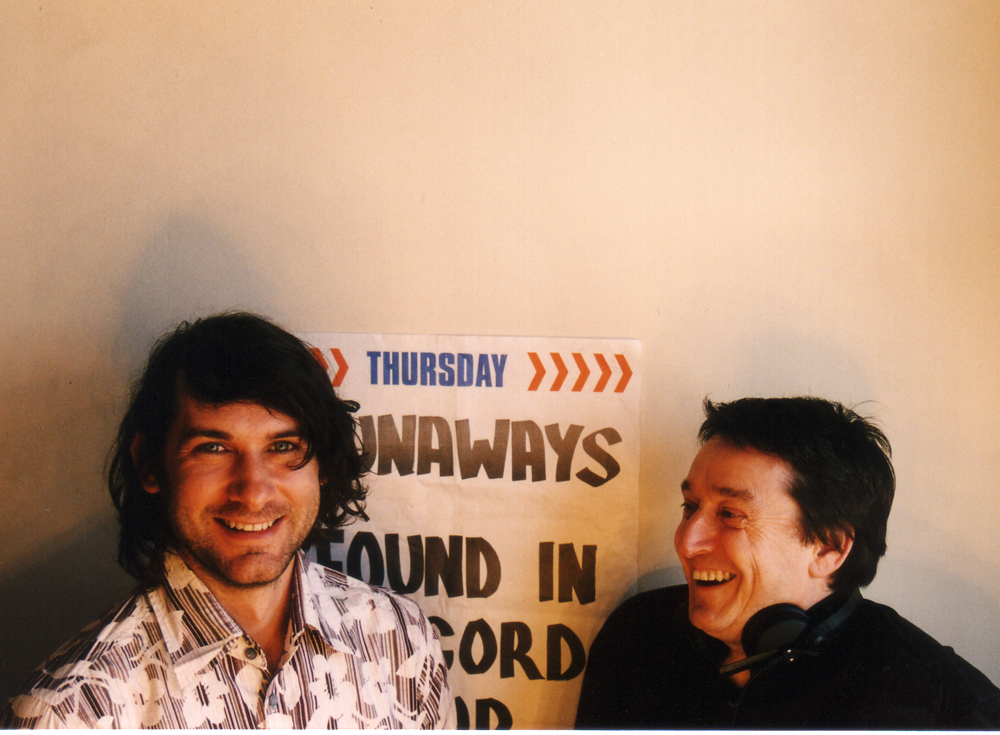

So we took the opportunity to talk to Frank & Bill about how they met in New York; the hard graft required to research Last Night… in the pre-internet age; their LowLife parties; and the trials and tribulations caused when your ideas are ahead of the technological curve…

You were both working in New York in the mid-1990s, how did you meet?

BB: I’d been working at Mixmag Update in the UK when a job opportunity came up to go and work in the New York office of DMC (Mixmag’s parent company). Frank was already living there and had been working as a stringer for Mixmag, i-D and other British mags. Anyhow, one day he came into the office to introduce himself and we immediately hit it off.

FB: I think the moment we became mates was when Bill came for Thanksgiving to my freak-filled house in Harlem and my mad landlord Jeffrey cooked a traditional Thanksgiving feast, which in his mind involved turkey basted with pancake syrup, and tinned asparagus soup (Campbells) with lots of sweet sherry added. Not a winning combination. Jeffrey is one of those classic New Yorkers of a certain vintage and he regaled us with camp tales of his 1970s/80s life in the city. A week later Bill and I were sitting on a barstool in Time cafe dreaming up a book on the history of disco.

How did the idea for 'Last Night...' come about? How easy was it to structure and how did you go about locating the interviewees?

BB: The book we wanted to write originally was about the history of New York dance music. There was such an incredible oral history tradition in the dance community that we couldn’t understand why no-one had documented it. But I think our idea didn’t really have a strong enough narrative to sustain it. We’d written this book for Ministry of Sound called The Manual and the editor, Doug Youngat Headline liked what we’d done and asked us if we had any ideas. We pitched them to him and he said, “Right ok. How about writing the history of the DJ?” That brought everything we’d talked about into focus and gave us a narrative thread to weave all these brilliant stories around.

FB: Once Doug set us the idea, we got megalomaniac on it and decided to nail it so comprehensively that no-one could follow us. A few books on the subject came out while we were writing it and we loved the fact they were generally really up-their-arse and academic – lots of critical theory and words like 'bricoleur', one even quoted Hegel and Nietzsche! Also, very quickly we realised the story is transatlantic – it's about the UK and US talking to each other. This was probably our trump card as we actually knew both sides of the story. Now of course we all know that American dance music started in Ibiza in 2010.

As for tracking people down, we used anything. There was no internet beyond weird bulletin boards, just people and phone calls. Interviewees would fill in gaps in the story and gave us their contacts and you'd trace the story to the source. I found Francis Grasso in the Brooklyn phone book and interviewed him in his local bar. Steve D'Acquisto was still working in music. The one original disco person we never tracked down was Michael Capello. So, if anyone fancies some detective work...

The NYC story centres on disco and hip hop. We split the field, so I was tramping around the South Bronx each day keeping it real with middle-aged B-boys while Bill was camping it up in the Village with all the pioneering disco queens.

How do you decide how to divide up the workload...writing partnerships are not that commonplace?

BB: It’s hazy now. However, what I do remember was we’d meet up at Frank’s flat in Clapham South every Friday and work together all day, fuelled by hash (me) and Chicken Cottage (both of us), going through everything together.

FB: We would write certain chapters each and then swap them back and forth, making them better each time. We're a killer combination because Bill is the world's most knowledgeable trainspotter whereas I'm clueless but a fancy-pants with the written word. He's anal and I'm pretentious.

You were back in London, running Low Life parties, had other gigs too - how did you find time for (a) more writing and (b) to launch djhistory.com? Did you sleep?

FB: In its 25-year existence Low Life has rarely been work. We collected an amazing dancefloor because the connecting factor was music and friendship. It just grew and grew by word of mouth because the music was always out-of-this-world but it was always a place to party not just nerd out. We knew all the party secrets! In retrospect the Low Life spirit was a perfect mix of the UK Balearic attitude and the dirtier, sexier, blacker, gayer New York version epitomised by Sound Factory.

BB: Well, the great thing about DJing and having some sort of ‘proper’ job, is they can coexist quite easily. I was certainly busy. I had a weekly column in the Big Issue and a monthly column in Mixmag. I was resident at Fabric. We’d just published Last Night…. But there was also time for other freelance bits of work and djhistory.comhappened pretty organically. We launched it in 2000, I think, but it wasn’t until we launched the forum in 2003 that it began to turn into something much bigger.

FB: DJhistory was a backbreaking slog. We were always about a year ahead of the technology, so we'd do something the hard way and then 12 months later there'd be a new way to do it effortlessly. Like use Amazon to distribute books, use print-on-demand, do a partnership with Juno rather than selling your own downloads, use social media to promote everything. Those possibilities only presented themselves when it was too late. We worked full-time on it for three years and burnt ourselves out. But an amazing experience in all sorts of ways.

As you did the interviews for the website, did you always envisage them becoming a book...and at what point did you decide to self-publish The Record Players?

FB: We carried on interviewing people for later versions of the book, largely to beef up the areas we'd not done justice to in the first edition, like Detroit techno, the UK warehouse scene, the various European scenes. And then – Bill mostly – just kept on going. We always gave people a different interview than they were used to, because we were asking them about their roots and their backstory rather than their latest single. It was really having them up on DJhistory that made us realise they could be stitched together to tell the story. It was great to have the whole history there as an oral history, because that's very much where it came from when we wrote Last Night. But this way, the academics and the serious spotters get it firsthand. By then we'd cracked book publishing, so we were able to put it out ourselves and roughly break even. And eventually earnt some money from it when Virgin picked it up.

Looking back, the website, the books, the parties - it all looks like a cohesive plan. Was it, or was it just an especially creative time where doors kept opening and you kept barging through them?

FB: Haha, we were flailing around from one moment to another. No plan, just doing stuff we wanted to. The constant thing with DJH was asking "how the hell do you do this?" how do you license tracks to sell as downloads, how do you make a barcode for a book?, etc etc, and we were too stupid to realise the barriers. DJH almost kept its head above water but we were so bad at business that we spent way too much time making lovely things and not enough time turning them into money.

The wider thing was that, as planned, we did manage to nail writing Last Night A DJ Saved My Life in a way that was impossible to follow, so we did become the "experts" in the field.

BB: The funniest thing was maybe the success of Low Life, because we did everything you’re not supposed to do in promoting. We told very few people, we didn’t publicly advertise anywhere, you had to know one of us to know about it, we never announced DJs in advance. But somehow all of those things became its USP and people sought it out precisely because it was a bit secretive. There was never a plan, until DJhistory started to take off and then we were more thoughtful about what we did, I guess. But before that, no, there was no plan.

Tell us about the other books DJH published - was becoming an independent publishing house scary or exciting? What made you stop?

FB: There are very few creative acts like making a book. Regardless of whether the words and pictures are yours or someone else's, it's a chance to express a vision in an extended and encapsulated way.

Vince Aletti's Disco Files was first and it's such a detailed account of that time – quite amazing to see the scene evolve almost record by record, club by club. And Vince hardly ever got it wrong. His judgment really stands the test of time.

The Disco Files was pretty successful, so we went mad and printed 5,000 copies of Raving ‘89 in one go and then realised just how much it costs to warehouse and move boxes of books.

But Raving ‘89 is a fabulous document of the early raves. Gavin Watson's photos are so personal and yet universal. Very proud of that one even though it was hard to get the world interested at the time. You can see its influence though – a couple of music videos recreated it almost shot for shot.

Boy’s Own speaks for itself, a real cultural document, especially when you see all the issues together. And no-one had a full collection, not even the Boy’s Own boys themselves.

Same with the Soul Underground collection Catch The Beat. It was a magazine that was first to write about so many scenes and again, amazing charts.

And there were books we nurtured but never got to publish cos we had to leave DJH aside and earn a living, like Graham Smith's We Can Be Heroes, all about the whole Blitz crew, which I edited and even named. That came out on Unbound eventually. Or Jane Fitz's history of pirate radio. Or Terry Farley's book, or Trevor Fung and Ian St Paul's book of scally stories and pre-rave Ibiza posters. So many we had to let go.

BB:It was both. I think we produced great books. I’m proud of all of them, but unfortunately, they all needed to sell well to keep the thing afloat and Raving ‘89 didn’t come anywhere near reaching its potential and Catch The Beat, the Best of Soul Underground, sold really badly and sunk us.

Have either of both of you got more books in you, or is that chapter closed?

FB: I'm currently writing a novel, believe it or not. It's a political ghost story. I can't say more than that. If the lawyers don't shut it down, it'll be hilarious.

BB: We are good friends. I crashed at his place last week. He’s the godfather of my daughter. So we see each other all the time. I’m pretty sure we’ll end up doing more stuff together, but I’m just not sure what that stuff will be right now. We were both rinsed out by running DJhistory.com; it was really quite debilitating,and we needed a break from each other and getting a bit of normality back in our lives for a while.

Can you list music books by other writers that (a) inspired you; or (b) are personal favourites?

FB: Lipstick Traces by Greil Marcus, Altered State by Matthew Collin, Once In A Lifetime by Jane Bussman, Rap Attack by David Toop, Disco by Albert Goldman, 33 Revolutions a Minute by Dorian Lynskey…most recently – Detroit 67 by Stuart Cosgrove …and Low Life by Luc Sante, not strictly a music book, but an amazing dive into 1890s New York City, and the name we stole to party with.

BB: The biggest inspiration for us was probably Matthew Collin’s book Altered State, because we were friends with him and that was the first post-acid house book of any note to be published. That encouraged us. There are other books that I think are amazing but aren’t relevant to what Frank and I do. Probably my favourite music book is Nico: Songs They Never Play On The Radio by James Young. Most musical narratives are about triumph, but this is about failure, a far more common occurrence in music. It’s so beautifully written. More recently Moby’s Porcelain is one of the funniest, truest music books I’ve ever read.