“Disco’s revenge,” was the way Frankie Knuckles mischievously described house, the style of music that was born in his club, The Warehouse, Chicago. The raw, machine-driven sound that Knuckles helped conceive has gone on to become one of the dominant forces in both club and popular music over the past 30 years, while Knuckles became one of the most sought-after remixers in club music, working with scores of stars, among them Michael Jackson, Chaka Khan and Diana Ross, earning him the undisputed tag Godfather Of House.

Born in the Bronx on January 18th, 1955, Knuckles grew up in an area surrounded by music (Luther Vandross lived down the street). As a gay man, he was one of the early beneficiaries of a rapidly changing society post-Stonewall and the nascent disco scene of which he was a part was a primary driver of those changes.

His entry into the music industry began as a teenager as he and his childhood friend and fellow DJ Larry Levan, worked for Nicky Siano at the Gallery in Manhattan, blowing up balloons and assisting their patron (one of their first jobs was to prepare a punch containing acid and distribute it to dancers). His first DJ break was at Tee Scott’s Better Days on W 49th St; he also had a spell at Continental Baths doing the lights and filling in for Larry Levan.

In 1977, Levan turned down a residency at a new club in Chicago called The Warehouse. Knuckles was only too happy to step. Mirroring his great friend Levan’s own rise at the Paradise Garage in Manhattan, Knuckles established himself as the guiding musical force in the city and as disco collapsed spectacularly towards the end of the decade, he began to experiment with his own edits, adding electronic oddities from Europe and employing drum machines that emphasised the beat in his live performances. “Sometimes I’d shut down all the lights and set up a record where it would sound like a speeding train was about to crash into the club,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “People would lose their minds.”

The term house probably came from the local record store Imports Etc, who would describe the music Knuckles played there by the this condensed term, although ironically, house music was never played at the Warehouse because it closed before local musicians began making their own productions. “I really felt that I became a part of something and that I belonged somewhere,” he recalled. “I got the same thing that David Mancuso got from the Loft and Larry got from the Garage: you knew it was yours. Everything you put into it and every time you opened your mouth, you know, ‘We need to do this, we need to put that in’. It was always being heard and recognised and adhered to.”

If The Warehouse lent the name, The Powerplant – alongside Ron Hardy’s Music Box – provided the foundry in which house music was forged with the city’s young producers eagerly passing on cassettes for Knuckles to play, the most influential of which was Jamie Principle’s ‘Your Love’ which was played years before release, with the pair subsequently collaborating on a string of club hits.

Although house music was driven by outdated electronic technology, principally Roland drum machines and rudimentary polyphonic synthesisers, Knuckles’ intentions revealed him as someone more ambitious than the average bedroom producer. The arrangements and instrumentation were often more redolent of his hero Trevor Horn than the ghetto tracks that had helped launch his career.

Under the tutelage of Def Mix’s Judy Weinstein with whom he signed in 1988 (arguably the most significant relationship of his career), he enjoyed significant successes as both producer and travelling DJ. He recorded two albums for Virgin in the early ’90s, with ‘The Whistle Song’ the only crossover hit, but continued to deliver consistently opulent remixes that always featured his trademark arrangements and made him one of the most in-demand club producers of his generation.

Although his stints at both the Warehouse and Powerplant were more influential, his greatest period as a DJ was arguably the two residencies he held back in his hometown New York when he returned back from Chicago: the Sound Factory, where he deputised for Junior Vasquez for a year and then the Sound Factory Bar, where he held a residency for several years.

“I would probably have to say that throughout my whole career the Sound Factory Bar is probably the best,” he told me in 2007. “The Warehouse was still a bit of a proving ground for me, I was still growing, and when I opened the Power Plant I ended up shutting down just so I could pursue a career in production, but moving back to New York City and playing at the Sound Factory Bar is when I really felt that I had an opportunity to show what I could do. The room was custom built around what I was about musically. The sound system was built to my specifications and the kind of music that I played and made. I didn’t get that anywhere else. I’m lucky to have had it!”

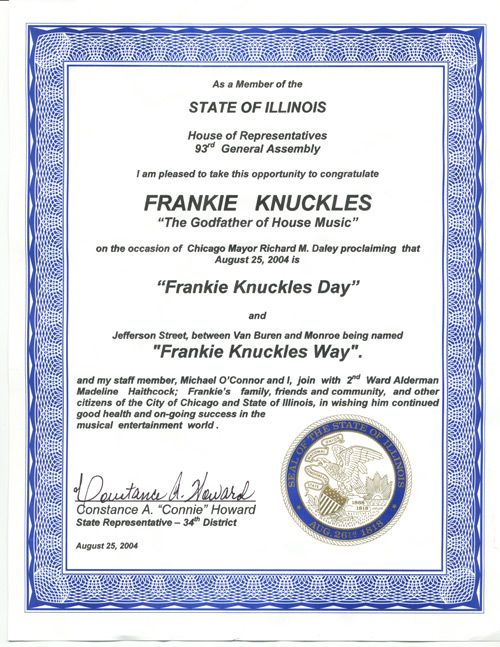

In 1998, Knuckles role in house music was acknowledged when he won the inaugural Grammy in the category Best Remixed Recording and in August 25th, 2004, thanks to a campaign backed by then Senator Barack Obama, South Jefferson Street in Chicago – the original site of the Warehouse – was renamed Frankie Knuckles Way.

Over the past ten years he had suffered some ill-health, having developed osteomyelitis after breaking some bones in his foot. He developed Type-2 diabetes, and in 2008, he had his foot amputated after he had refused to let up in his punishing DJ schedule. Nevertheless, his death was sudden and unexpected. His final gig was at the Ministry Of Sound in March 2014.

It’s fitting that he carried on playing right up until his death. He didn’t know anything else. When he was asked if he could ever conceive of retiring he bluntly replied, “No. It’s just so much of what I do and who I am. You know there are certain things in your life that are like mainstays? They’re always there. They are things that you never think about. I think it’s a part of the same thing for me. It’s a mainstay.”

“I think Frankie more than anybody could capture emotions,” says Chicago record producer Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley. “It wasn’t so much a technical thing with him or what beat he was mixing, it was more what record the people wanted to hear after the record he was playing, and what was gonna take the energy up, up, up. That was one of the things that made you want to go and hear him.”

Words: Bill Brewster

Defected presents House Masters Frankie Knuckles is out 26 April 2015 (2CD and digital) on Defected Records - order from iTunes and order the CD / t-shirt / bundle from DStore now. 100% of the profits will be donated to the Frankie Knuckles Fund.