WORDS: NICK GORDON BROWN

Gathering in a field to listen to music is a centuries-old pastime, with plenty ofevidence of ancient festivals, both religious and pagan. The Pythian Games in Ancient Greece began in the 6th century BC, alternating with the Olympics, but with the emphasis on art and dance as much as sport. It’s unlikely that Strings Of Life was on the playlist, or Chris Martin made a series of unannounced guest appearances, but it is highly likely that repetitive beats featured.

The music festival as we understand it today is very much a product of the 1960s, an era of counter-culture celebrations whose influence continues to be felt to this day. The Monterey Pop festival took place in California in June 1967. Widely regarded as the first high profile music festival of the modern era, it came just a couple of weeks after the Beatles released their Sgt Pepper album, and these two landmark events effectively kickstarted the first summer of love. However, this was more than a hippy gathering, with the line-up notable for its musical diversity – contemporary dance music was represented by Otis Redding, who put in an electrifying performance.

Although Monterey may have been the first, few would argue that the 1960s festival that had the most impact was Woodstock. Held at Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in New York State in August 1969, and billed as ‘3 Days of Peace & Music’, it has been widely heralded as the high watermark of 1960s counter-culture. So big were the numbers that descended on the site, estimated at close to 500,000, that it became a free festival by default as the organisers simply couldn’t cope with the number of ticketless fans. As with Monterey, the line-up was more diverse than is often remembered, and Sly & The Family Stone’s 3.30am funk-fuelled Sunday morning set is seen as one of the festival’s major triumphs – watching this incendiary clip, it’s easy to see why.

Whilst Woodstock is more often than not the first name dropped when the roots of the modern day festival scene are discussed, arguably just as influential have been carnivals. Though grounded in historical religious celebrations (many of the most famous carnivals take place in February to coincide with the period leading up to Lent), the latter day carnival is a blaze of colour and noise, typified by outrageous costumes, parades and a spirit of escapism that certainly infuses the best festivals. The most famous is the annual shindig in Rio, which attracts an estimated two million revellers daily. Rio Carnival is dominated by the ritualistic sounds of samba and batucada, a rhythmic assault on the senses that will strike a chord with dance music fans worldwide.

Although less internationally renowned, the annual carnival in Colombia’s northern coastal city of Barranquilla comes close to rivalling Rio for both numbers and spectacle. The musical soundtrack is once again dominated by percussive, tribal sounds rooted in Colombia’s best known musical export, cumbia; and the more explosive, afro-influenced champeta. These sounds have made an international impact over the years. Colombian record label Disco Fuentes is celebrated as having one of Latin music’s most treasured catalogues; English soul and jazz musician Will Holland (aka Quantic) lived in Colombia for several years to soak up its indigenous music and work with multi-talented local musicians; and Balearic DJs such as Nancy Noise have championed tracks by the likes of Wganda Kenya, whose tracks have had reissues on labels like Soundway and Mr. Bongo.

Many carnivals take place in city centre locations, and Europe’s most celebrated is London’s Notting Hill Carnival, which takes place annually over the August bank holiday weekend. Originally conceived to recreate the spirit of Caribbean carnivals in this corner of west London, while this may still be at the heart of the event, it has mushroomed in many different directions in its six decades. Sound systems are central to Notting Hill, and if there is one that is synonymous with broadening the musical spectrum beyond reggae and dub to take in soul, funk, disco, hip hop, house and more, it’s Norman Jay’s Good Times. A Carnival staple for the best part of 30 years, Norman exited stage east a few years ago, disillusioned with the knock-on effect of creeping gentrification on both the area and carnival. But this clip from 2012 shows why it was such a hot ticket for so long, uniting as it did numerous London sub-cultures around one big red bus.

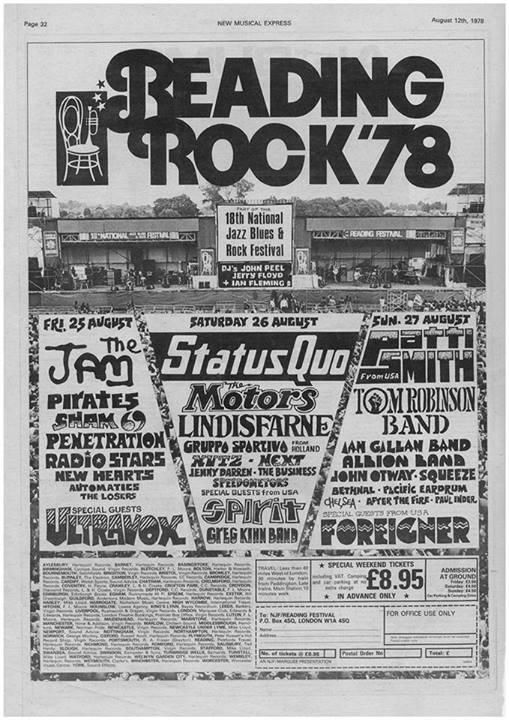

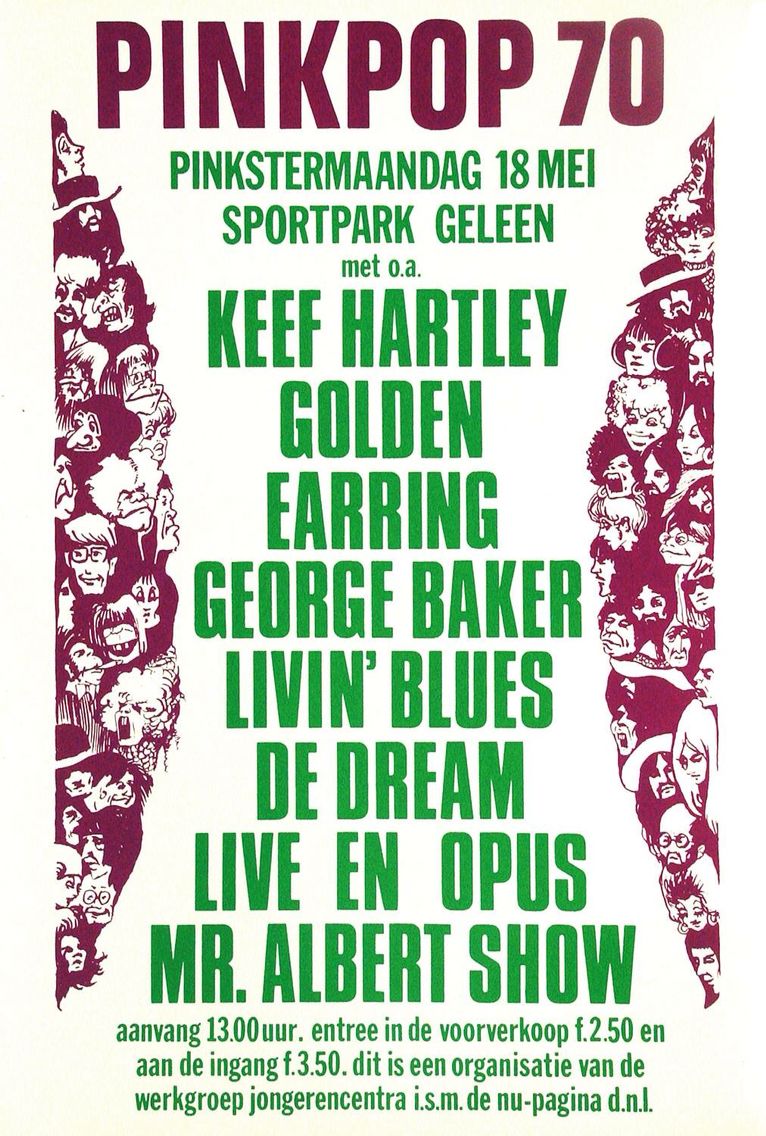

If Woodstock was the hippy dream personified in vibrant living colour, for many that dream died just 4 months later when violence erupted at the Rolling Stones-headlined Altamont festival in California, concluding in the murder of attendee Meredith Hunter at the hands of the Hell’s Angels who were acting as ‘security’. With the tragedy infamously caught on film, this is often cited as the reason why major festivals in the USA went through an extended fallow period, barely registering on most music lovers’ radars through the 1970s and well into the 1980s. In Europe, however, something was stirring. The Isle of Wight Festival ran from 1968-1970, but was a victim of its own success, the council effectively revoking the organisers’ license for 1971 in the belief that the island couldn’t handle the crowds (this has not been a problem since the festival was re-born in 2002). However, the likes of Roskilde in Denmark, Pink Pop in Holland and Reading in England survived and thrived to varying degrees.

The Glastonbury Fayre’s first edition was in 1970, with a young David Bowie headlining in 1971. It then took a break until 1979, becoming a near-permanent fixture from the early 1980s onwards. Word of mouth saw artists increasingly queuing up to play, while increased media exposure saw demand for tickets grow exponentially. The 1994 edition saw a pivotal moment for both the festival and dance music. The rave scene had become massive (see below), only to come up against numerous hurdles erected by the panicked authorities. Some ravers had teamed up with another scourge on those authorities, new age travellers, in an attempt to keep the party going; the new age travellers were already a fixture at Glastonbury. Looking at a way to attract and welcome clubbers and ravers, Michal Eavis and his team booked Orbital.

The Hartnoll brothers’ set on the Other Stage has become the stuff of legend, as 40,000 festival goers, many of whom had never previously witnessed a live act without a guitar, were entranced by their electronic masterclass – all topped off by the head torches they wore to see their equipment, but which were to become an iconic trademark. What’s more, it was beamed live into several million living rooms as UK broadcaster Channel 4 showcased the festival for the first time. A year later, Glastonbury had a dedicated dance tent, today it has dance arenas and fields galore, with every clubland genre and subgenre imaginable represented. Orbital have made several further visits, while the likes of Fatboy Slim and the Chemical Brothers have become much-anticipated regulars.

Orbital’s all conquering Glastonbury performance was a much needed shot in the arm for an outdoor rave scene in the UK that had been fighting an increasingly futile battle with the law, especially with the introduction that same year of the Criminal Justice Bill, which gavethe police the power to shut down events featuring music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. It may seem hard to believe now, but such was the moral panic that the rave scene had engendered, that it was deemed necessary to outlaw a musical genre.

The road to this showdown began in 1989. The previous year’s acid house summer of love in the UK had been played out for the most part in traditional city centre venues. Its successor took place in an array of fields and disused warehouses sourced by ever more enterprising promoters, who constantly outwitted the police. In this pre-internet age, motorway service stations were the meeting points where ravers gathered awaiting the phone call that would tell them where the party had been set up. In the London area, the recently opened M25 London Orbital motorway provided ideal access to many a Home Counties field discovered by promoters such as Sunrise, Energy, Biology and World Dance; further north, the scene centred around the Lancashire mill town of Blackburn, where events such as Hardcore Uproar and Live The Dream attracted thousands.

For the party goers, it was a life-changing experience. For the authorities, they couldn’t look beyond what they saw as the pure lawlessness of the mix of drugs, cars abandoned on motorway hard shoulders and buildings being broken into. The early 1990s saw a split. On the one hand, as licensing laws were relaxed to encourage ravers back into legal venues, promoters such as Fantazia, Raindance and Universe began to throw large scale officially sanctioned events. The thrill of the chase had gone, but the parties were guaranteed to go ahead unchallenged. On the other, however, were those who saw 1989 as the beginning of a brave new world, an alternative lifestyle, and sound systems such as Spiral Tribe and DiY continued to run unlicensed events. In stark contrast to the big money that had started to swill around the rave scene, where for some the music clearly wasn’t the motivation, the free party scene, as it became known, arguably presented the police with their biggest challenge yet.

Things came to a head in May 1992. Police chose to close down the established Avon Free Festival. A mix of new age travellers and sound systems who had been heading for the event diverted to nearby Castlemorton. As media coverage of a large, impromptu free party increased, so did the numbers attending. A week long event ensued, leading to lurid newspaper headlines and questions in the Houses of Parliament. The battle lines had been drawn, and the way paved for the Criminal Justice Bill and its ban on repetitive beats. A series of marches against the bill were organised in London, attended by tens of thousands. The bigger the numbers, the harder the crackdown. The bill became law in November 1994.

Meanwhile in America, a very different type of travelling festival was on the road. Lollapalooza was the brainchild of Perry Farrell of alternative rockers Jane’s Addiction. The summer of 1991 saw the band joined on their farewell tour not only by a diverse range of fellow artists, from goth queen Siouxsie Sioux to rapper Ice T; but also by circus acts, art displays and pop up info stalls for political and counter-cultural groups. Lollapalooza burned bright through the mid-1990s, ended, then was revived in the new century as a one site event with international parties added to the mix. Arguably it helped provide the inspiration for Coachella, which this year celebrated its 20thanniversary, and whose line-ups read like a who’s who of 21st century music.

Fast forward to 2019, and the choice for festival goers worldwide is mind-blowing. Undergo ‘decommodification’ in the desert at America’s legendary Burning Man. Join fellow househeads at Turin’s stunning Parco Dora and dance in a transformed industrial wasteland. Take a mini holiday on the Croatian coast with Defected, Love International or Outlook. Party in an abandoned iron mine at Sweden’s Norberg festival. Wade through websites to check out the accommodation, the food options, the comedy tent, the pop-up stores, the yoga and meditation classes. Alternatively, simply take in a one day event where you can enjoy dozens of your favourite acts (and stumble across a dozen new ones) in one hit, all for the price of a couple of routine nights out.

Woodstock and co may have set the festival template, and Glastonbury refined and modernised it. Carnivals undoubtedly inspired additional glamour and spectacle. However, there’s a strong argument that the electronic music explosion and the mass participation events they triggered paved the way for contemporary festival culture. Many of the late 1980s / early 1990s generation are now actively involved in festival organisation, promotion and curation. Perhaps most notably, Cream founder James Barton did a deal with the world’s biggest live music company, Live Nation, for the Creamfields brand. This in turn led to Barton being appointed their President of Electronic Music, and two years later Rolling Stone magazine anointed him “the most influential person in EDM.” Barton then chose to strike out on his own again, forming Superstruct Entertainment, a behind the scenes festival superpower that has interests in events worldwide, including the likes of Elrow and Sonar in Spain, SW4 and Boardmasters in the UK, Sziget in Hungary and Hideout in Croatia.

Rob Da Bank began the leftfield club night Sunday Best in the 1990s, which led to a label of the same name, with Da Bank eventually landing radio shows on leading UK stations Radio 1 and 6Music. From this position of strength, he launched the award-winning Bestival and Camp Bestival events. Another pioneer who has worked his magic for three decades now on the experimental fringes of the electronic scene is Andrew Weatherall. This year sees the seventh edition of the Convenanza festival he curates in the French town of Carcassonne. Meanwhile one of his equally revered contemporaries, Gilles Peterson, is about to launch his We Out Here festival in the UK, and the Ricci weekender in Sicily, having already established his Worldwide events in France and Switzerland.

A new generation of events is now coming through, created by those who have grown up with festivals as commonplace, and have a strong sense of what makes a party unique. One of the most celebrated boutique festivals on the calendar is Lost Village, the brainchild of Jaymo and Andy George, much loved club / radio DJs, label bosses and promoters. They attribute much of Lost Village’s success to their having both attended and played at all manner of festivals worldwide. Similarly, the Team Love crew behind the likes of Love International in Croatia and Love Saves the Day in the UK is made up of a group of like-minded souls who have played a part in programming and managing stages at numerous high profile festivals (including Glastonbury), with co-founder Dave Harvey also an established DJ and label manager with the Futureboogie collective.

There are now numerous events built primarily around DJs and electronic acts, but equally even the biggest of the more rock/pop-based festivals now have a vibrant dance element at their core. Repetitive beats lost the battle but won the war. In the words of 19th century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche: “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”